Week 1: Introduction

This week, we introduce the course and discuss three Fundamental Problems of Scientific Inquiry, which will guide our thinking about data analysis this semester.

Reading

No reading due before our first class. See Week 2 for next week’s reading.

Problem Set

No problem set due before our first class. See Week 2 for next week’s problem set.

Class Notes

“Normal science” (Kuhn 1962) is an iterative process of (1) creating theories about how the world works, (2) testing those theories against evidence, and (3) refining our theories in light of the evidence. This is all very hard work. Because while the world of theory is all very tidy and knowable, the world inhabited by humans is messy and full of unknowable things. Any scientist who wants to test their theories against evidence will quickly run into three Fundamental Problems of Scientific Inquiry. I call these problems fundamental because they are inherent to the process of knowledge creation, and cannot be fully dispelled no matter how fancy one’s statistical toolkit. Let us consider each in turn.

The Fundamental Problem of Measurement

Our theories about the world often involve concepts and ideas that we cannot observe directly with our senses. Political scientists are interested in particularly nebulous concepts—like democracy, polarization, freedom, ideology, representation, warfare, alliances—ideas that are all quite sensible when described in words, but lack an obvious method for categorization and measurement in the real world. In statistical terminology, something like a person’s ideology (Converse 1964) is a latent characteristic, something that we cannot observe directly. Instead, we observe behaviors that we think are influenced by a person’s ideology—which campaign they donate to, how they respond to survey questions, how they vote on bills, etc.—and infer their ideology on the basis of those observed characteristics (Barber 2021). But it’s important to remember these observable measures are always imperfect glimpses at the theoretical concepts we’re trying to understand.

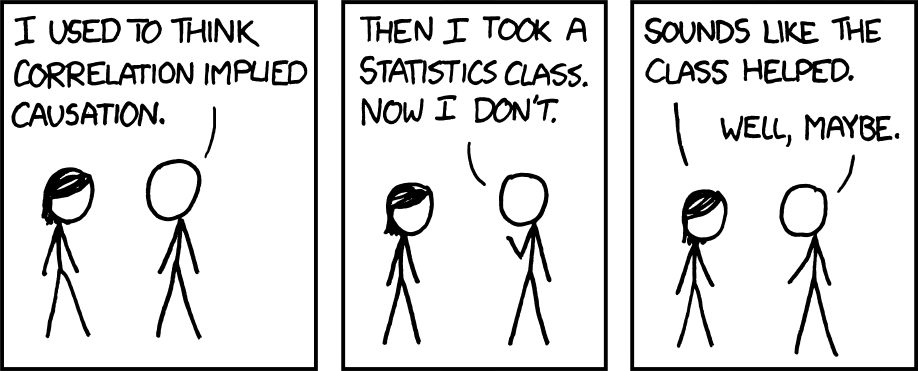

The Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference

Scientists are rarely satisfied with measurement alone. We don’t just want to describe the world (“Candidate X won the election”); we want our theories to explain why the world works the way it does (“Candidate X won because she spent more on TV advertising”). Fundamentally, every such causal claim is implicitly a counterfactual claim (“If Candidate X had spent less money on TV advertising, she would have been more likely to lose.”). But the Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference is that we can’t observe counterfactuals. We only know what happened in this universe, and can never know with any certainty what would have happened if circumstances were different. This makes testing causal claims rather difficult, because the best we can do is look at average differences across different data points.

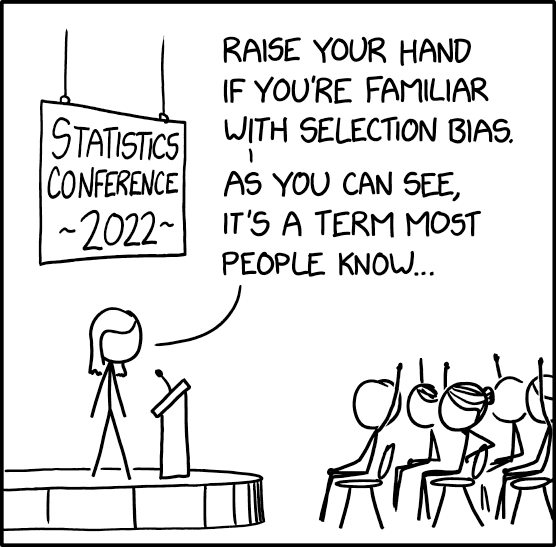

The Fundamental Problem of Samples

Scientists strive to develop general theories about the world; a theory is more useful if it can be fruitfully applied to a large number of cases and situations. But we rarely if ever observe our entire population of interest, so we can never say with certainty that the patterns we observe in our dataset will hold true for the population at large. This is particularly problematic if our observed sample is selected in a non-random fashion, making it unrepresentative of the larger population.

One can think of these three fundamental problems as three different kinds of missing data problems—whether it’s a latent characteristic, a counterfactual, or observations not included in your dataset—there is some information that we do not observe directly, and so we have to predict what it might be on the basis of the information we do observe. Fortunately, we have a number of methods for credibly making these sorts of inferences. We’ll learn several of them in the first half of this semester!

Additional Resources

Gelman, Hill, and Vehtari (2021) is a bit more advanced than the content we cover in POLS 7012, but chapters 1 and 2 helped motivate the “three challenges of statistics” (website).

Berinsky (2017) is a nice overview of the challenges of measuring public opinion using polls, emphasizing that who we ask and what we ask are equally important considerations.

See the Rubin Causal Model for a more detailed discussion of the potential outcomes framework and the Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference.

Bradley et al. (2021) is a beautiful exploration of the “Paradox of Big Data”, demonstrating why large samples are not necessarily better samples.